On June 3, 2025 I was invited to make a statement during a public hearing at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium organized by the Special Committee on the European Democracy Shield. The hearing was titled "Enforcement of the EU Digital Rulebook and political advertising in the context of foreign interference: understanding Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) and disinformation as systemic risks to electoral processes and public discourse".

My intervention can be watched in full here:

Text of my prepared remarks:

Fact checking is sometimes falsely presented as "censorship" when it is the exact opposite: it is journalism that adds information. The vast majority of work we fact checkers do is not determining what "The Truth" is but is simply pointing out what is provably false.

As a Belgian who has co-founded an American fact checking company that has worked for Meta and ByteDance, both in the United States and here I am quite aware of the different attitudes that exist about regulating speech.

Still, most citizens, including me, are rightfully suspicious of any laws that seek to hide or suppress information outside some well-defined exceptions like child pornography.

On the other hand, legally requiring information disclosure is much more widely accepted: nobody says food or cigarettes are being censored because there are laws that require ingredient lists or cancer warnings. So why should digital services be any different? Especially if they use algorithms to track people's emotions and beliefs to serve them content they haven't explicitly searched or asked for.

One of today's topics is "identifying gaps in legislation". When making rules it is important they are clear and unambiguous. Traffic law doesn't say "don't drive too fast", it says "don't drive faster than 50".

The DSA, for example, says:

Providers ... shall put in place reasonable, proportionate and effective mitigation measures ... ensuring that an item of information, whether it constitutes a generated or manipulated image, audio or video that appreciably resembles existing persons, objects, places or other entities or events and falsely appears to a person to be authentic or truthful is distinguishable through prominent markings when presented on their online interfaces.

But what is "reasonable", "proportionate" and "effective"? And what about "distinguishable" and "prominent"? And why make it ambiguous if an "item of information" is limited to being an "image, audio or video"? AI or human generated text can just as easily falsely present things that appear authentic and truthful and so can a false caption under a real photo.

Let's take another concrete example and look at the system of Community Notes on X, which Meta is also rolling out on their platforms in the U.S.

Under that system, a select group of users can add notes with context under posts where they think it would be useful. The other users in the program can then vote if they find the note "helpful" or "not helpful". They are not actually voting if the note or the post are true or not. If a note gets enough votes it becomes visible to all users. But the system also requires that there is consensus among enough voters who have previously voted differently on other notes.

To compare it to the European Parliament, it would be like having a rule that a vote can't pass unless at least some people in every political group have also voted "yes".

But that is not how facts work: the shape of the Earth doesn't change even if social media users can't find consensus about it.

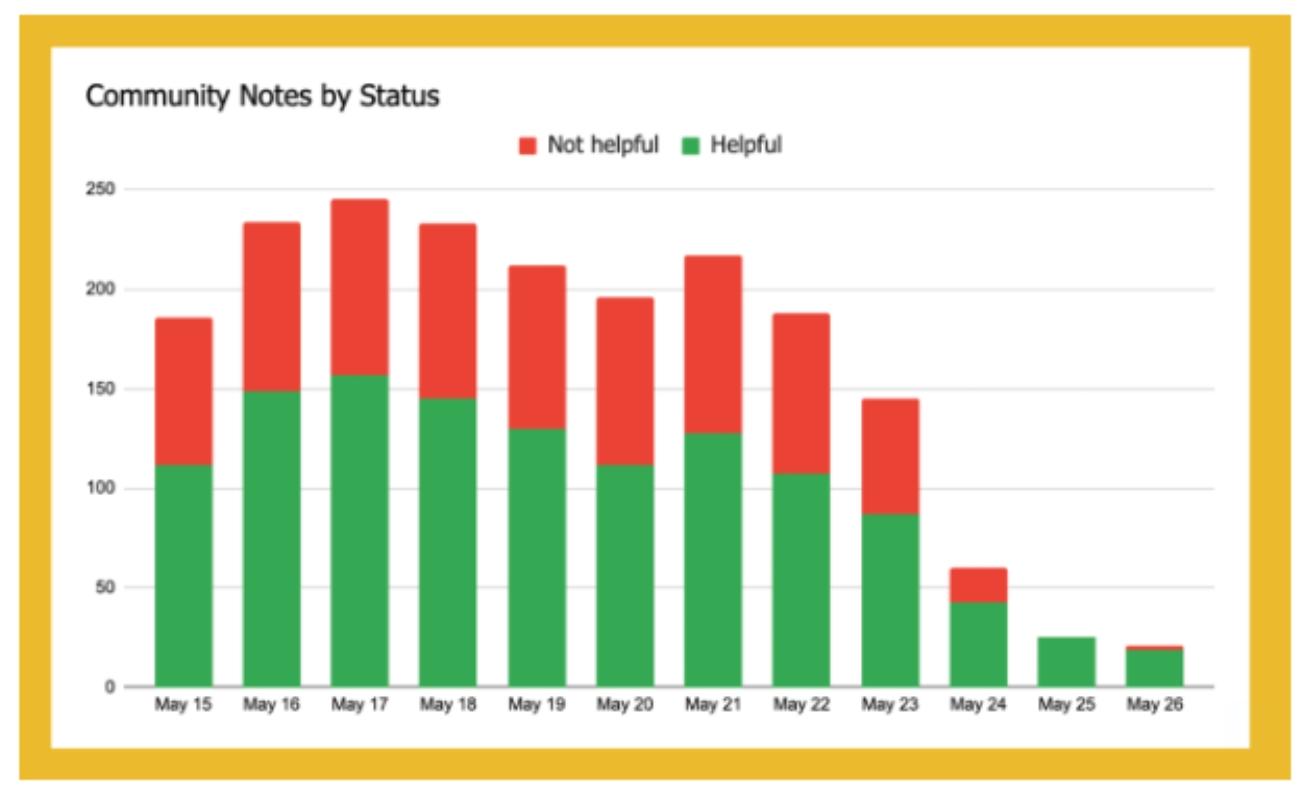

This system slows things down and suppresses many notes with true information: it can take hours or days to collect enough votes to be able to calculate a consensus. And it seems designed to hide notes that would benefit one side in very partisan debates, regardless of the accuracy of the information.

Case in point, this post by President Trump seen by over 80 million people which contained clearly false information: it attracted over two dozen proposed notes that gathered thousands of votes but not a single note became visible because no consensus could be reached.

In practice, over 90% of proposed notes never become visible to the public and the ones that do often appear well after the false information has already been seen by vastly more people than will ever see the Community Note. According to research, besides links to other posts and wikipedia, the third-most cited source in notes are fact checks, which proves that in many cases the information is readily available but it gets hidden or delayed.

When notes are about philosophical, religious or political topics the algorithm must by necessity process, derive and store data about the voting user's views on those topics: how else can you calculate who disagreed with who? This is something explicitly prohibited by the GDPR outside a very narrow scope of exceptions. But even apart from that, is it a good idea to let private companies collect data about political beliefs based on social media behaviour? Even Meta once seemed to have doubts about that, given their reaction when Cambridge Analytica did it.

Also, can you really call a system "effective" if it can go down for almost five days and nobody notices the difference? This actually happened on X last week: due to a technical error no notes were shown under posts at all, even if consensus had been reached. But users were so used to not seeing Community Notes appear even under posts with clearly false information that hardly anybody noticed the difference.

(Image source: Indicator newsletter)

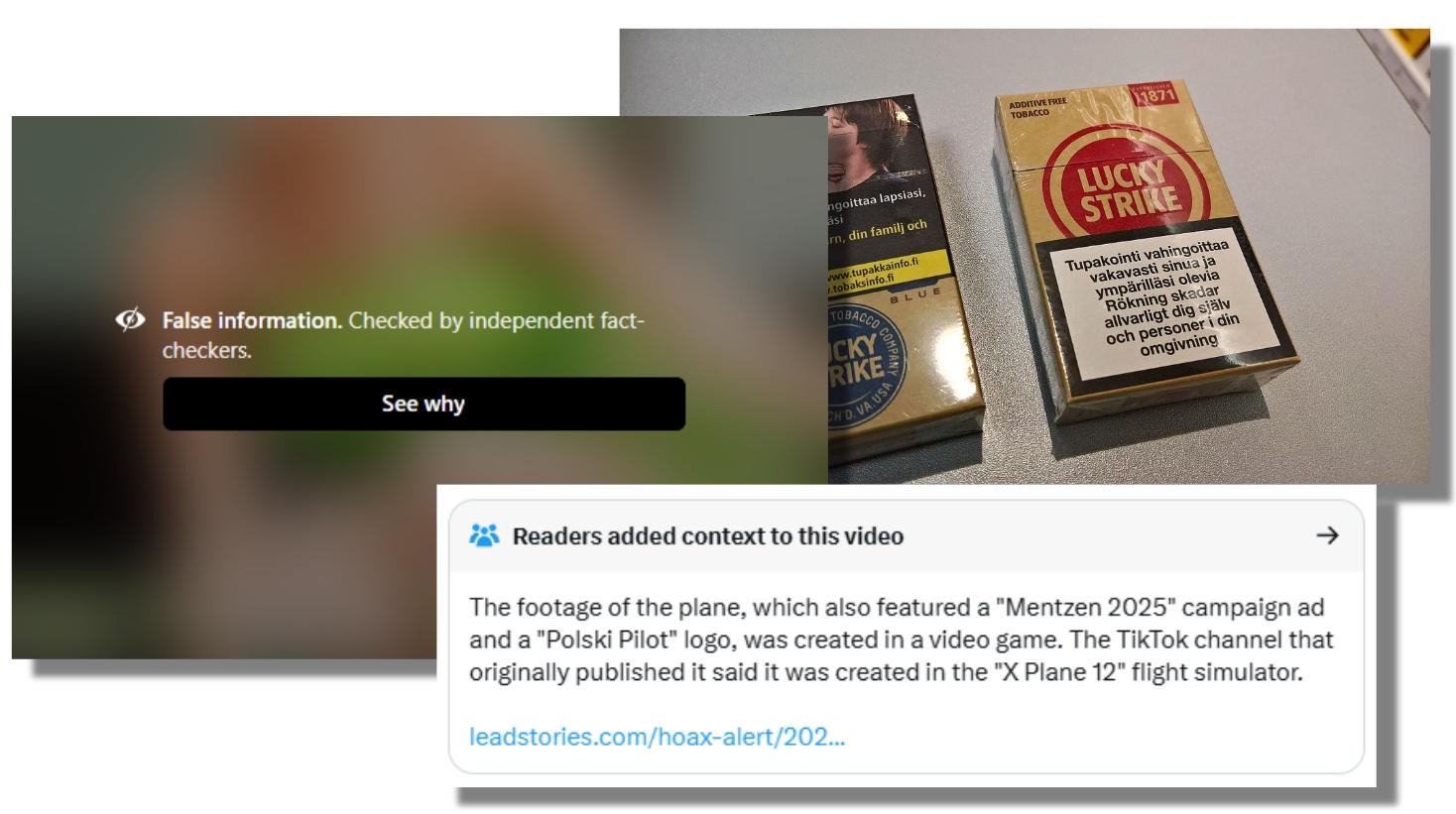

The DSA also calls for "markings" that are "prominent" to make false information distinguishable. Under Meta's fact checking system images and videos labeled by fact checkers are covered up with a "screen" that implies fact checkers are responsible for hiding this content and offering users the chance to see it anyway. Users are also offered a chance to see the fact check but this takes more clicks and as a result only a very small fraction do.

Zero clicks to get irritated, two clicks to see false information and three clicks to see what is wrong with the information: is it any wonder some people don't like this?

That is one thing Community Notes on X are currently doing better: when a note does become visible, the information is presented right below the claim, in a similar font size and using neutral language.

Also note some other policies at Meta seem to be designed to avoid showing certain information to users even when it is available: Community Notes added by U.S. users are not displayed in Europe while European fact checkers are discouraged from labeling U.S. publishers (even though they are technically not banned from doing so).

In summary, if I could offer any advice:

Have clear definitions for "reasonable", "proportionate" and "effective"

For example: you fail if more than x percent of the y most viewed posts in a given period contained false information that was not labeled within z hours of time, or you didn't retroactively notify and inform users who saw such information. Speed matters:labeling false election information after the polls have already closed is not effective.

Have a clear definition of what "prominent markings" should look like.

A light grey font on a white background, fluffy language like "Imagined with AI", irritating messages like "according to fact checkers this is misleading" or information that only becomes visible after you click or tap something does not mitigate anything or inform anyone.

Explicitly put "free speech" in the legislation.

To head off censorship accusations or misunderstandings, rules dealing with misinformation should explicitly say they impose no obligation to delete, remove, hide, suppress, ban or cover anything just because it is false.

Keep the "lowest common denominator" in mind.

All platforms and search engines will observe what the lowest level of compliance is that their competitors can get away with. That will become the standard. The drone I own for hobby photography weighs exactly 249 grams because European drone legislation begins to impose certain restrictions the moment a drone weighs 250 grams or more, so manufacturers responded by making them lighter.

Surely measures protecting democracy shouldn't be lightweight.