Does exposure of blood to ultraviolet light rid the body of coronavirus? No, there is no evidence that it does. The fact that ultraviolet light has been shown to kill the virus on surfaces does not mean that it does the same thing in people.

The claim appeared in a post (archived here) put up on Facebook on April 24, 2020. The post read:

For all you dummies that have absolutely no idea what Trump is talking about... UV light is injected into the body as a disinfectant to kill bacteria and viruses and this has been used for a while now. Just because it's called a "disinfectant" doesn't mean it's Pine-Sol Y'all really showing your asses today. -- words by --John Lewis

Ultraviolet Blood Irradiation (UBI) is a procedure that exposes the blood to light to heighten the body's immune response and to kill infections. With exposure to UV light, bacteria and viruses in your bloodstream absorb five times as much photonic energy as do your red and white blood cells.

CNN News (World News) fake news and MSNBC{News Junkies} MSNBC you are the ones going to get people hurt! The president not once said to inject yourself with disinfectant, IE Bleach, pin sol etc... stop watching this fake news media shit please everyone! Go watch Fox News Tucker Carlson Tonight Sean Hannity

Thank you Rob for the information....

Now please everyone share this...."

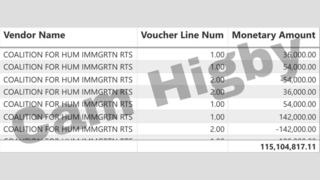

Here is what the post looked like at the time of this writing:

First, a reminder that Trump did not say that people should inject themselves with ultraviolet light or disinfectant. Instead, he urged a federal official to look into the possibility that ultraviolet light or disinfectants might prove useful in combatting the coronavirus that has swept across the world in recent months.

The reference to ultraviolet blood irradiation (UBI) is based on this tweet, which links to this paper, published in 2017:

He is an example of UV light injection. Used as a disinfectant to kill viruses and bacteria.https://t.co/GSdAXHmyN5 pic.twitter.com/3j9Lw7uilZ

-- Mel Q (@littllemel) April 24, 2020

The paper, written by Michael R. Hamblin, associate professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, notes that UBI "was hailed as a miracle therapy for treating serious infections in the 1940s and 1950s." But interest in the procedure diminished with the introduction of antibiotics.

The procedure was also used to treat polio, but the introduction of the Salk polio vaccine in 1955 drew attention further away from UBI, Hamblin notes.

Now, as infections caused by multi-antibiotic resistant bacteria have become more common, more costly and more difficult to treat, some researchers are taking a fresh look at UBI. Hamblin, who is also editor-in-chief of "Photobiomodulation, Photomedicine, Laser Surgery, wrote:

We would like to propose that UBI be reconsidered and re-investigated as a treatment for systemic infections caused by multi-drug resistant Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [two broad categories used to classify bacteria] in patients who are running out of (or who have already run out) of options.

"Patients at risk of death from sepsis could also be considered as candidates for UBI. Further research is required into the mechanisms of action of UBI. The present confusion about exactly what is happening during and after the treatment is playing a large role in the controversy about whether UBI could ever be a mainstream medical therapy, or must remain side-lined in the 'alternative and complementary' category where it has been allowed to be forgotten for the last 50 years."

In an email to Lead Stories, Hamblin noted that, "although UBI has mainly been studied for bacterial infections it is also effective for viral infections such as hepatitis C and influenza. It works by stimulating host defenses not by killing the viruses. There have been circa 400,000 treatments carried out by practitioners who are generally not mainstream doctors. It is still unclear why it has not been more accepted."

He pointed to the April 24 Twitter video as an example of how ultraviolet light could be used on blood:

Still, the idea of using ultraviolet light as a treatment for COVID-19 has not gained acceptance from the mainstream medical community, and has not impressed Dr. Michael Saag, an infectious disease expert at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

"Not a great option," he said in an email. "Technically difficult, and even if it could be done, the blood isn't where the virus hangs out."

He noted that a similar approach was touted early in the HIV epidemic, before the development of lifesaving anti-HIV drugs like protease inhibitors, and that the approach killed several people. In those cases, doctors heated the blood -- hyperthermia -- in an attempt to kill the virus.

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the federal government's lead AIDS research agency, conducted an investigation and concluded that it had found "no clinical, immunologic or virologic support" for the use of hyperthermia to treat AIDS or Kaposi's sarcoma, an AIDS-related cancer.

Further, the agency said, "neither does there appear (to be) any support for further human experimentation in this area at this time."