Does a "new" scientific paper definitively show that people aged 50-64 have a 1-in-19.1 million chance of dying from COVID-19? No, this is not true. The paper, which is not new as it was posted June and studies a one-week period in May, has yet to be peer-reviewed and is not to be used to "guide clinical practice," according to a warning at the top of the pre-print publication. Also, the research has been updated, dramatically dropping the numbers presented in a widely circulated report. Moreover, the paper is an "estimation" -- a hypothetical -- that acknowledges its numbers would be baseless if there were spikes in cases, which there has been. The ratio is per person contact, assuming a person only has contact with one other person.

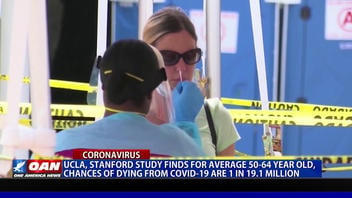

The claim appeared in a video (archived here) published on YouTube by One America News Network, or OAN, on Sept. 4, 2020, titled "UCLA, Stanford study finds for average 50-64 year old, chances of dying from COVID-19 are 1 in 19.1M." It opened:

A new study from medical researchers at UCLA and Stanford University found the chances of contracting or dying from coronavirus are much lower than previously thought.

Click below to watch the video on YouTube:

The research is real and is called "Estimation of Individual Probabilities of COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death From A County-level Contact of Unknown Infection Status." It has been published as an article on the preprint server medRxiv. The research is not, however, "new," as the OAN story claims. It is from June 6, 2020, and it relied on data from one week May from the 100 largest counties in the United States. As of Sept. 9, the U.S. has the highest case count (6.31 million) and death total (nearly 190,000) from the virus in the world.

The chief claims in the piece by OAN's Pearson Sharp are these, referring to the authors of the research:

They found that an average person in an average county has a 1 in 3,836 chance of getting infected with the coronavirus, and that's without wearing a mask or doing any social distancing. Even the odds of being hospitalized are vanishingly small, even for someone in the at-risk category. For an average person between 50 and 64 years old, the chances of getting the virus and needing hospitalization are 1 in 852,000. And for that same person who's at risk, the chances of dying from coronavirus are 1 in 19.1 million."

The OAN report, which suggests the research shows there is no need for lockdowns or some other safety measures, let alone trust in "so-called expert Dr. Anthony Fauci," makes no mention of the fact that it has yet to be peer-reviewed -- a critical step in authenticating scientific and medical research. It also pays no mind to other scientific or medical experts, who say it has red flags.

The 24-page paper looks at single contact between individuals and the risk such contact has in transmitting the virus. The authors, Dr. Rajiv Bhatia, clinical assistant professor of primary care and population health at Stanford University; and Dr. Jeffrey Klausner, adjunct professor of epidemiology at UCLA, acknowledge there are shortcomings to the research -- something ONA, which portrayed it as definitive, left out of its report.

OAN uses terms like "current risk" and "are" to suggest this research applies to the present time. The paper by Bhatia and Klausner, however, analyzed a short time, one week ending May 30, when COVID-19 cases were down. They have since gone up overall, and the research even notes that the numbers provided in it would not be accurate if there was a spike in cases. There were 1.8 million cases in the U.S. on May 31, and now there are more than 6.3 million.

The OAN report also leaves out the fact that the paper's numbers, even without safety precautions urged by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, refer to a "random contact" with another person.

For example, the paper reads under "Materials and Methods":

Our objective is to estimate the probability of acquiring COVID-19 infection from a "contact" with a random individual of unknown infection status. We conceptualize this probability under steady state conditions (e.g. no epidemic growth or decline) as a function of individual susceptibility, the current reported case incidence, accounting for undetected infection, the share of infection transmission occurring without a known contact, the chance of transmission per contact (e.g., the secondary attack rate), and the duration of infectiousness, accounting for pre-symptomatic transmission."

Bhatia replied to a Lead Stories inquiry on Sept. 9, 2020, writing:

The paper, currently under peer review proposed a "methodology" for predicting the probability of serious outcomes from on a single contact of average exposure intensity and at a particular symptomatic case incidence rate. The risk estimate per contact from an average contact was estimated to be 1 in 6.7 million in an average big county in late May 2020. Risk varies significantly by county and over time. The predicted risk estimate was the range of observed death. The 1 in 19 million figure comes from an earlier draft.Since testing now produces a large number of asymptomatic case we can no longer assess risk using this exact method and are revising the methodology to account for this.

The authors wrote that they looked for other studies looking at the "risk" of getting the new coronavirus, but found a dearth of research. So, they wanted to add a layer of research.

In its abstract and the end of the paper, the authors wrote:

Estimates of the individual probabilities of COVID infection, hospitalization and death vary widely but may not align with public risk perceptions. Systematically collected and publicly reported data on infection incidence by, for example, the setting of exposure, type of residence and occupation would allow more precise estimates of probabilities than possible with currently available public data. Calculation of secondary attack rates by setting and better measures of the prevalence of seropositivity would further improve those estimates.

Among other cautions about the research, it treats everyone as equals, despite findings that various health conditions, lifesyles, different precautions and varying housing situations have an impact on infection and death rates.

For example, the paper states:

For this analysis, contact means any substantive exposures that happen in a community, household, workplaces, or group living situations. Examples of substantive contacts outside households might include dining with a friend or business contact, working in a shared office space or having close or physical contact without the types of precautions now recommended for prevention of infection transmission (e.g. avoiding handshaking, embraces, wearing a mask or indoor ventilation). We do not consider contacts to be short-term events, such as passing by a person on the street. Contact within households involves habitual and typically unprotected close physical. We understand that attack rates will vary across such diverse exposure settings."

Also, there's the study of "risk," something Dr. Susan E. Hassig, an epidemiologist at Tulane University, said is risky in itself. According to the Mercury News report, Hassig said:

...unlike say, HIV, which is spread through sex or drug needles, it's often a mystery how a person was infected with the new coronavirus. Was it talking to a friend at the park or lunch with a co-worker?

And people don't have a long history with this new coronavirus from which to develop a sense of risk.

"It's not like the risk of being struck by lightning," Hassig said. "We tally that over years, sometimes decades. We've been doing the coronavirus for four months, so we're in a really challenging position where it seems like there's lots of information but it's not like it's data that's usable to estimate risk."

In the same Mercury News story, Bhatia acknowledges as much:

"This is the best we could do without more data partitioning the risk in different settings...Yes, the risks are probably lower than most people might perceive. But we could, with better data, make this much more precise."

As for the OAN story, which runs two minutes and 50 seconds, it calls out Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, as a "so-called" expert. The report also states that the paper -- again, not yet peer-reviewed and considered controversial or flawed by other scientists and medical experts -- shows the case for closing down all or parts of the economy "falls apart."

Bhatia declined to comment on this, writing "we do not take on the question of the value of intervention."

Near the end, Sharp says regarding the 1-in-19.1-million risk factor for 50-64 year olds:

These figures come after a reveal from the CDC itself that of all deaths attributed to the coronavirus, just 6% actually died from the virus itself. The other 94% had severe underlying medical conditions."

That statement has already been debunked by Lead Stories.

He ends the piece with this opinionated claim:

Combined with this latest data, the case for keeping the country locked down falls apart and revelas the risk to the American public appears much lower than so-called experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci had claimed."

None of the OAN story is conclusive or fact. For example, Fauci, who has served under six presidents since 1984, is considered by most scientists and medical officials to be the nation's leading expert on infectious diseases, including the novel coronavirus. And saying the case for closing parts of the economy and other protective measures against COVID-19 "falls apart" is conjecture on the part of OAN.