Does a new study confirm the COVID-19 vaccine is not 95% effective? No, that's not true: It's not a study at all but a comment in The Lancet, and it says vaccines do work at a high efficiency level, the author told Lead Stories.

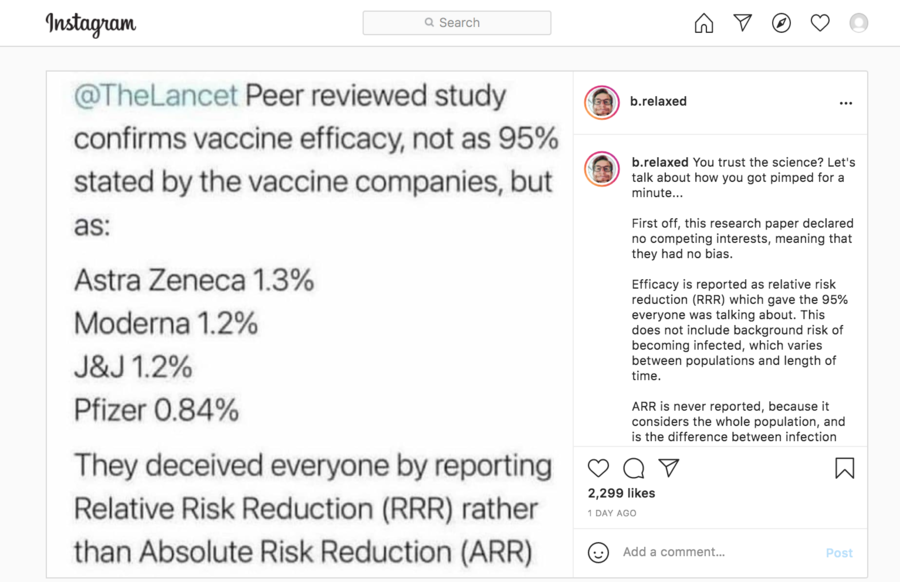

The claim appeared as an Instagram post (archived here) on May 26, 2021. It opened:

"@TheLancet Peer reviewed study confirms vaccine efficacy, not as 95% stated by the vaccine companies but as: Astra Zeneca 1.3% Moderna 1.2% J&J 1.2% Pfizer 0.84% They deceived everyone by reporting Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) instead of Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR)"

Social media users saw this post:

(Source: Instagram screenshot taken on Thur May 27 20:11:29 2021 UTC)

The Lancet comment published April 20, 2021, "COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and effectiveness--the elephant (not) in the room," seems to be the one referred to in the Instagram post. The full Instagram post reads:

You trust the science? Let's talk about how you got pimped for a minute...

First off, this research paper declared no competing interests, meaning that they had no bias.

Efficacy is reported as relative risk reduction (RRR) which gave the 95% everyone was talking about. This does not include background risk of becoming infected, which varies between populations and length of time.

ARR is never reported, because it considers the whole population, and is the difference between infection with and without a 💉

We aren't told about the ARR because they are purposely ignored because they give a much different story, which is much less impressive.

Your Pheyezur schmaccine just went from 95% down to 0.84% effective.

There are many different ways a researcher can lie with statistical reports. Google the book title "How to Lie with Statistics."

Did I mention that that is one of Schilly Billy's favorites?

Piero Olliaro, professor of poverty-related infectious diseases at the University of Oxford and one of the authors of The Lancet comment, explained its intention and results to Lead Stories via email on May 27, 2021:

It is extremely disappointing to see how information can be twisted and how divisive discussions have become especially on COVID-19 vaccines, as they obviously overlap with general vaccine hesitancy and antivax segments of the population.

Bottom line: these vaccines are good public health interventions. Importantly, the effects of vaccination should not be seen merely as reducing individual risk, but its effects on reducing the risk in the entire population, with all its ramifications - reducing stress to health systems, hospital bed occupancy, societal costs, effects on economy, etc... a long list.

We do not say vaccines do not work. We say vaccines do work, and add considerations about intrinsic vaccine efficacy and their effectiveness when used in different populations.We say that:

It is incorrect to compare vaccine based on clinical trials conducted in different conditions, using relative risk reduction (RRR calculated as explained in the paper), and assume vaccines with lower RRR do not work well enough. Studies should therefore report also absolute risk reduction (ARR, calculated as explained in the paper).

Why? The RRR is a measure of vaccine efficacy in preventing disease in those at risk of getting infected and becoming ill; the ARR is a measure of vaccine effectiveness in a population where a certain proportion of individuals will get diseased without vaccine. ARR is more difficult to understand, but can be conveniently translated in NNV (number need to vaccinate = how many people need to be vaccinated in a population with a given background risk of getting covid-19 without vaccine to prevent one more case of covid-19.)

The article explains these concepts with numerical examples from vaccine trials, and that even vaccines with relatively lower RRR are totally worthy.

These numbers are evidence of effectiveness, since even the least "effective" vaccine (Astra-Zeneca and J&J with RRR of ~67%) you just need to vaccinate ~80 people to prevent one case in populations where just under 2% of people get covid-19 within a certain period of time. This also shows that 2 vaccines with very similar, high efficacy (RRR ~95%) can have different effectiveness depending again on the risk of covid-19: NNV for Moderna vaccine ~80, Pfizer ~120 (the latter was studied in the population with the lowest risk of all).

Olliaro and his colleagues published this response to criticism:

It is customary yet inappropriate to compare vaccine efficacies and make policy decisions solely on relative risk reduction (RRR) from clinical trials with different protocols in populations with different background risks for COVID-19--unless vaccines were tested within a common trial as advocated by WHO.3

RRR focusses on those who benefit from the vaccine and, although more stable across event rates (levels of risk for COVID-19), its interpretation requires knowing the actual background risk and its variability. Absolute risk reduction (ARR) considers all individuals and translates conveniently into number needed to vaccinate within a population with a given risk, but its public health significance varies with the risk. For any given RRR, ARR is higher when event rates are higher--eg, earlier into a vaccination programme, or in high-risk groups--and decreases as risks decline.

Both ARR and RRR are helpful to assess trade-offs between benefits and harm, because evidence is still limited on whether or how they change across the range of individual responses and risks related to age, comorbidities, behaviours, and level of exposure, as well as over time--with risk of COVID-19 decreasing with vaccination scale-up or altering due to virus variants.