Do Amish people never vaccinate their children? Have there never been any outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in Amish communities? No, neither is true. While a meme uses the sarcastic hyperbole of the Amish being "wiped out by a plague" to mock the effectiveness of vaccines, the meme relies on two false beliefs: one, that Amish people never vaccinate their children -- they can and they do; and two, that Amish communities have never been impacted by vaccine-preventable diseases -- there have been several documented outbreaks in Amish communities.

The text of the meme paired with an image of the man in a hat began circulating on social media in November of 2020. Since then, many additional images have been used for this meme. One example is this post (archived here) published on Facebook on July 31, 2021. The text in the meme, with the word vaccinate obscured with emojis, reads:

REMEMBER THE PLAGUE THAT WIPED OUT THE AMISH BECAUSE THEY DON'T VACCINATE THEIR CHILDREN?

YEAH, ME NEITHER

This is what the post looked like on Facebook at the time of writing:

(Source: Facebook screenshot taken on Tue Aug 3 19:12:48 2021 UTC)

The claim that Amish people don't vaccinate their children is put forth as if this is a faith-based restriction that is true for every Amish community. This is not true as explained on page 324 in the 1993 book, "Amish Society" by John A. Hostetler:

The misunderstandings that exist between the Amish and local health authorities were well illustrated in the outbreak of polio that occured in a small community of Amish in 1979. According to newspaper accounts, the health authorities reported that the Amish refused to take immunizations on religious grounds. The accounts also stated that the Amish bishops refused to permit the use of polio vaccine. Both of these assumptions were false.

If the Amish are slow to accept preventive measures, it does not mean they are religiously opposed to them. The Amish are cautious, and they are viscerally conservative about accepting government programs of any kind, including health plans. Their reluctance stems from not knowing what sources of knowledge to trust and from waiting for consensus and hints from among their own spokesmen. They dislike publicity, and whether a bishop or the head of a family is involved, no one likes to take action in a crisis without the knowledge, and preferably the approval, of others. In the case of the polio outbreak, after a series of visits by health officials, the Amish arranged for mass immunization sessions in their homes and schools, The objection to polio immunization was finally overcome when a lay member argued that the Amish would not want to become the cause of other persons getting the disease.

A report titled, "Vaccination Usage Among An Old-Order Amish Community In Illinois" was published in the December 2006 edition of the The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. An anonymous survey about vaccines was distributed to members of the Amish community in Arthur, Illinois, through a community newsletter. The majority of families in that community said they were vaccinating their children. From the report:

This study reveals that Amish households do not universally reject vaccines, and Amish objections to vaccines are not typically for religious reasons. Additionally, the decision to accept vaccinations is based on multiple factors and might be influenced by information on vaccine safety provided by trusted medical providers. These data demonstrate that previous reports of Amish vaccination status derived from previous studies should not be generalized to all Amish communities.

The study finding that 90% of respondents had received vaccinations and 84% of families had vaccinated all of their children was surprising, on the basis of our past understanding of Amish vaccination rates. No comprehensive study has examined vaccination coverage among Amish in the United States. Common methods of assessing vaccination status (eg, telephone surveys9 or college entry surveys) lack the ability to include the Amish as part of the study population because the Amish do not have telephones or attend college. Small community-based surveys of Amish in Pennsylvania1,6 and Wisconsin10 demonstrated that the vaccination rates of children in these Amish communities were too low to prevent vaccine-preventable diseases, if introduced, from spreading within the community. This study demonstrates that previous reports of Amish vaccination status should not be generalized to all Amish communities.

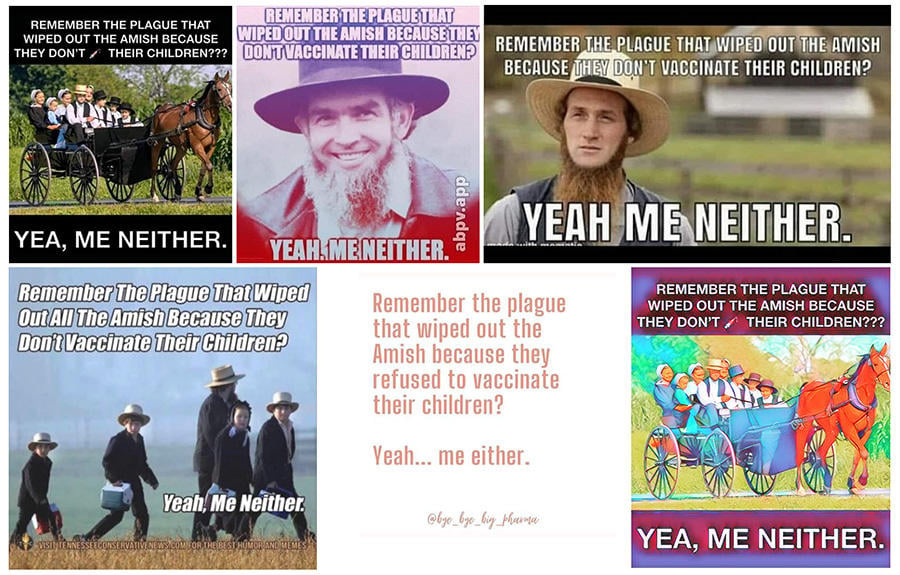

Below is a collection of memes with a variety of images and nearly identical captioning which were all circulating in the summer of 2021. In some cases the word vaccine has been replaced with a syringe emoji or obscured in an effort to avoid algorithmic detection of vaccine related content.

(Source: Lead Stories collection of Facebook screenshots taken on Tue Aug 03 20:19:39 2021 UTC)

There are many case reports of outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases in Amish communities: pertussis (whooping cough), rubella, measles, polio in 1979 and 2005, and Haemophilus influenzae Type b (Hib). A June 24, 2014, article on NPR.org titled, "Measles Outbreak In Ohio Leads Amish To Reconsider Vaccines," tells of the experience of a local county health department nurse, Jacqueline Fletcher, who had received a phone call from an Amish woman reporting cases of measles in her home and a neighbor's. Fletcher's first time seeing the disease in her career wound up being the start of the largest measles outbreak in the country in 20 years.

The largest outbreak of measles in recent U.S. history is underway. Ohio has the majority of these cases -- 341 confirmed and eight hospitalizations. The virus has spread quickly among the largely unvaccinated Amish communities in the center of the state.

Fletcher collected samples the afternoon she arrived. A county worker drove them immediately to the state health department and quickly confirmed the measles. The next day, Fletcher says she was on a call with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"I remember the first conversation we had with the CDC," she says. "The fellow said, 'You have to get ahead of this.'"