A viral video that was digitally altered to make it appear that U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was slurring her words and drunk has raised questions about what social platforms can do to limit fake content's spread. Since Lead Stories was the first of Facebook's 3rd-party fact checkers to flag the faked video, we can now share how effective our work was on slowing its distribution. When we tagged the video as false, it was like shooting a missile out of the sky. The rate of shares, likes and views of the content plummeted, according to data collected by our Trendolizer system.

Even with the revelation that the video was not real, hate mail showed some people still wanted to believe the top Democrat in congress is a drunk. Just an hour after publication of our debunk article concluding that an editor used the tempo filter to slow it down without changing the pitch of Pelosi's voice, our inbox was filling with messages including:

Bullshit.. Nancy Pelosi was drunk and jacked up on pills. Been there Done that... Nice try buddy

Shut the f**k you dumbasses

I am f**king pissed off. I watch that crazy bimbo Nancy Pelosi slurring her words, not even knowing who is the president, and rambling on in absolutely incoherent speech on live F**KING TV. You asshole are fake news, and have no business fact checking anything. You are a communist left wing hack, and have zero credibility. F**K YOU VERY MUCH.

She has an Alcohol problem and shouldn't be in a leadership position. This isn't the first video we've seen her fumbling her words. Stop covering over her incompetence!! Stop putting your opinion on my news feed. They are lies!!

Not a single email thanked Lead Stories for publishing the truth. For more reactions, read the comments at the bottom of our story titled "Fake News: Video Does NOT Show House Speaker Pelosi Drunk As A Skunk."

More than a few media critics expressed alarm at the spread of the faked video and have attacked Facebook's decision to not just delete it from its servers. Our analysis, however, shows its pace of distribution and consumption was not really that hot. In fact, it was rather tepid compared to much of the content we encounter every day in our battle against fake news.

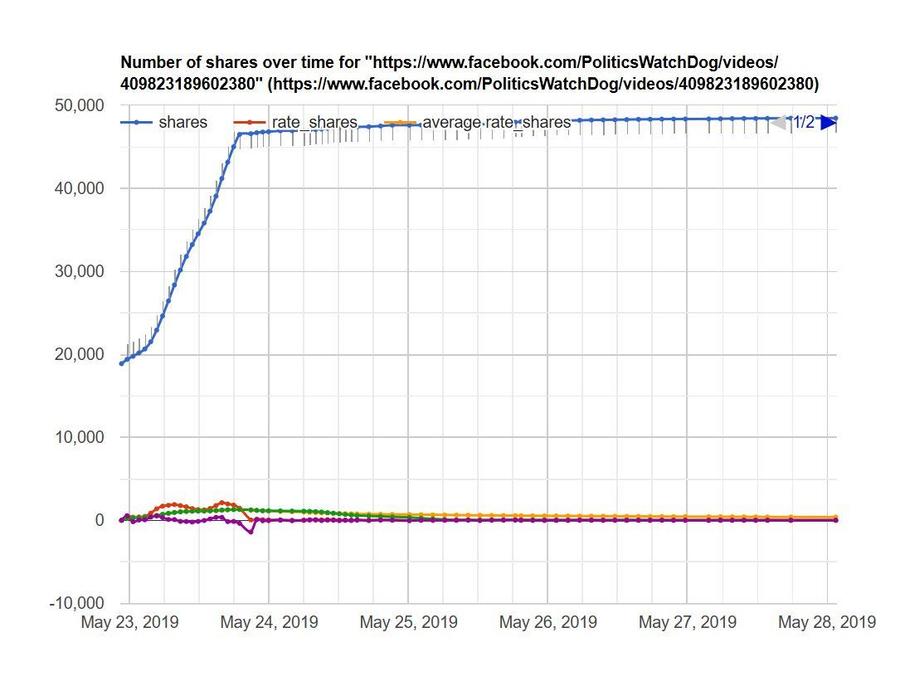

Politics Watchdog, a Facebook page with 35,000 followers, posted the doctored video several hours after Pelosi's mid-day appearance at the Center for American Progress conference in Washington, D.C. Wednesday, May 22, 2019. Lead Stories' Trendolizer engine began tracking it at 1:35 a.m. EDT on March 23, about 14 hours after Speaker Pelosi delivered her remarks that the fake video's publisher targeted. By then, the video had been liked 3,848 times, shared 18,881 times, and viewed 688,087 on Facebook. (This is not counting the copies posted on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, and other platforms.)

The Pelosi video's rate of shares, likes, and views per hour were not particularly high.

It ranged between 1,000 and 2,000 shares per hour for the first day, peaking at 2,124 shares between 3 and 4 p.m. EDT on Thursday, May 23. A rate of 10,000 shares each hour or higher is typical of a viral video, so this one fell short. This is not surprising since the page that initially published it has just 35,000 followers. Pages that are successful in getting quick viral traction usually have one or two million followers. Again, this was a small page by those standards.

Although we use our Trendolizer tools to alert us to potential viral fake news targets for our writers to debunk, the Pelosi video did not rise to the level of virality to warrant attention that Thursday morning. I first noticed it when one of my Facebook friends -- a journalist in Nashville -- questioned it with a post on her timeline.

The video seemed wrong immediately. I've been editing audio and video with digital software for two decades and I know it is easy to alter the tempo without changing the pitch. Some editors call it the "drunk filter." It just takes two or three clicks of a mouse to make a speaker -- in this case THE SPEAKER -- sound intoxicated. Just as I was comparing the C-Span version of the Pelosi's remarks with the questionable one, I saw the Washington Post analysis. By 6 p.m. PDT (I am in Los Angeles) I was confident I had our story ready. After publishing at 6:07 p.m. PDT (9:07 p.m. EDT), I flagged the Politics Watchdog video with the Facebook tool we use for fact checking that platform. My next task was to search and flag copies on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and websites. We've identified and flagged 30 in all.

The impact of our false rating was immediate and decisive, as shown by this graph of the trajectory of sharing.

At the time Lead Stories flagged it as false, the video had 46,519 shares, 8,692 likes, and 2,268,188 views. Soon after we published, the peak rate of 2,124 shares per hour measured just two hours earlier was throttled to a trickle of just 43 shares an hour. Facebook was serving up an alert to anyone clicking the share button, informing them that the content had been rated false by a fact checker along with a link to our article explaining why it is false. Each of those 46,519 Facebook users who had already shared the post were getting the message. Facebook also dramatically reduced the display of the content on user timelines.

Despite all of the media attention about the video, the Political Watchdog video flat-lined on Facebook.

It was a hot topic on cable and broadcast news, as well as with online blogs and newspapers, but the traffic tanked. Four days after Lead Stories first flagged the video as false -- triggering all of the actions designed by Facebook to limit the spread of fake content -- it was shared less than 2,000 times, a very slow average rate of 20 times per hour. It gained less than 3,000 additional likes, an average of just 43 per hour. It was viewed only 570,000 times more in those subsequent four days, a not-so-hot rate of 6,000 per hour.

Critics who contend that Facebook should have immediately removed have immediately removed all incidences of the doctored videos from its servers may have a difference opinion after a few days in the trenches in the war against fake news. Doing so would have made our challenge tougher, like a whack-a-mole game. Copies would pop back up and we would try to find them and flagged them. Facebook users can seek out the videos now if they wish, but at least they will be informed. Nothing Lead Stories or Facebook can do would change if someone chooses to reject that information because it conflicts with something they wish to believe.