Do U.S. student loans cost the government over $60 billion more to service than those loans bring in during the year? No, that's not true: According to experts, the cost of servicing student loans is a much smaller figure than $60 billion, which means it could not result in a $60 billion difference compared to how much those loans bring into the government. Plus, the amount of money student loans bring in is constantly fluctuating and is dependent on a number of factors, including the wide range of loan repayment options.

The claim appeared in a Facebook post (archived here) published on October 25, 2021. It had a screenshot of a tweet that reads:

Wait was nobody going to tell me that US student loans cost the government over $60B more to service than they bring in a year??? They could literally be cancelled this second and the gov would have *more* money

The screenshot also shows that the user who made the tweet replied to it by saying that the information came from the U.S. Department of Education Federal Student Aid Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report.

The Facebook poster also made a claim about deflation in the caption, which will not be addressed in this fact check.

This is what the post looked like on Facebook on October 27, 2021:

(Source: Facebook screenshot taken on Wed Oct 27 21:44:05 2021 UTC)

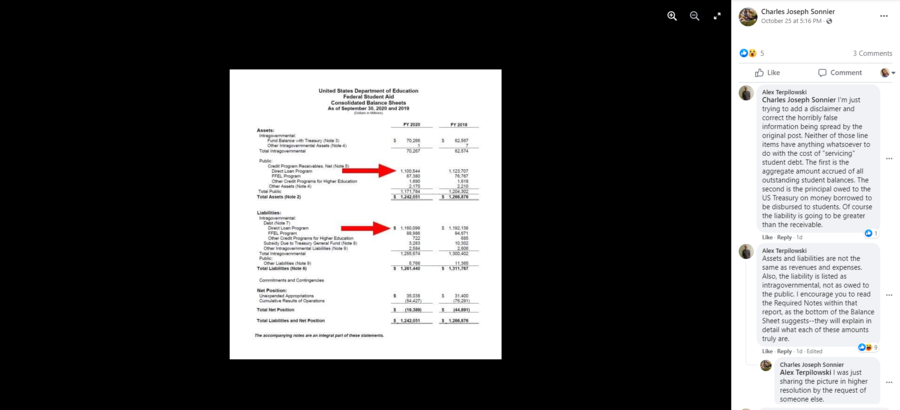

The claim appeared to be referring to the roughly negative $60 billion difference between the "Direct Loan Program" asset ($1.10 trillion) and liability ($1.16 trillion) figures on page 169 of the Federal Student Aid (FSA) report. This was pointed out in this comment replying to the Facebook post, screenshotted below:

(Source: Facebook screenshot taken on Wed Oct 27 19:04:55 2021 UTC)

When applied to student loans, the term "servicing" is usually associated with companies contracted by the federal government that handle services related to a borrower's loans. As explained here, the loan servicers are paid a monthly fee. In the claim, "servicing" seems to be conflated with all funds associated with giving out student loans.

Consequently, the claim does not explain the numerous components that comprise the figures in the chart. More information about the figures is found in the notes to the chart, included in the report. Note 5 of the report introduces information about the public assets of the Direct Loan program here. The note then describes the various fluctuating elements of the Direct Loan program that are not mentioned in the claim, including interest expenses and revenue and subsidy expenses. It also clarifies the risk in estimating the long-term costs of the Direct Loan program:

Due to the complexity of the Direct Loan program, there is inherent projection risk in the process used for estimating long-term program costs. As stated, some uncertainty stems from potential changes in student loan legislation and regulations because these changes may fundamentally alter the cost structure of the program. Operational and policy shifts may also affect program costs by causing significant changes in borrower repayment timing. Actual performance may deviate from estimated performance, which is not unexpected given the long-term nature of these loans (cash flows may be estimated up to 40 years), and the multitude of projection paths and possible outcomes. The high percentage of borrowers in Income Driven Repayment Plans has made projection of borrower incomes a key input for the estimation process. This uncertainty is directly tied to the macroeconomic climate and is another inherent program element that displays the interrelated risks facing the Direct Loan program.

Loans written off result from borrowers having died, becoming disabled, or declaring bankruptcy. The interest rate re-estimate reflects the cost of finalizing the Treasury borrowing rate to be used for borrowings received to fund the disbursed portion of the loan awards obligated.

Similarly, the debt figure shown in the chart is not fleshed out in the claim. Note 7 of the report explains the intragovernmental debt of FSA during fiscal year 2020 and debt related to the Direct Loan program:

FSA borrows from Treasury's Bureau of the Public Debt to fund the disbursement of new loans and the payment of credit program outlays and related costs. During FY 2020, debt decreased 2.9 percent from $1,287.5 billion in the prior year to $1,249.8 billion. FSA makes periodic principal payments, after evaluating the cash position and liability for future outflows in each program and pays interest, as mandated by the FCRA.

Approximately 92.8 percent of FSA's debt, as of September 30, 2020, is attributable to the Direct Loan program. The majority of the net borrowing activity (borrowing less repayments) for the year was designated for funding new Direct Loan disbursements.

FSA also borrows from Treasury for activity in the Other Credit Programs for Higher Education. During FY 2020, TEACH net borrowing of $59 million was used for the advance of new grants and repayments of principal made to Treasury.

There are other reasons why the claim is not accurate. In an email to Lead Stories on October 27, 2021, Sarah Abernathy, executive director of the Committee for Education Funding, said:

The Facebook posting isn't correct - the federal government doesn't pay more than $60 billion more to service loans than it brings in in a typical year. In fact, in FY 2021, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that administrative costs for all federal student loan programs was a little over $3 billion (see table 4 of this CBO report: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-07/51310-2021-07-studentloan.pdf)

One thing to keep in mind is that because of the pandemic, the government stopped collecting payments on student loans in spring 2020 and still hasn't started, so the 'cost' of the program (ie, how much it costs in administration plus the cost of new loans being given) is certainly more than has been coming into the program since then. The FY 2020 costs were estimated about the same, but slightly lower: see https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2020-03/51310-2020-03-studentloan.pdf

This CBO report (https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-10/57412-Federal-Credit-Programs.pdf) talks about the projected cost to the federal government of all the credit programs, including student loans. Depending on which of two estimating practices you follow, the student loan program either costs money or makes money. But it doesn't cost money because the government pays loan services a lot, it costs money because the federal government makes loans to students that may not all be repaid because some are in income-driven repayment programs where remaining loan balances are forgiven after certain periods, some are defaulted, interest rates change, etc.

Frank Ballmann, director of federal relations for the National Association of State Student Grant and Aid Programs, said in an email to Lead Stories on October 27, 2021:

While I don't have direct insight into the US Department of Education (ED) numbers, I think it's safe to say the claim is both false and out of context.

- While I don't know what the current contracts call for, generally loan servicers get paid $1-$3 per month per borrower depending on the borrower's status (school, grace, repayment, etc.), so that's $12-$36 a year. Let's say $30 on average. If you estimate there are 40 million borrowers out there, the cost would be $1.2 billion. Nowhere near $60 billion

- For the last year-plus (i.e., since the national emergency was declared in March 2020), payments have not been required. So while the payments possibly would be near $1.2 billion (voluntary payments are still accepted; I have no idea how many are being made), in a normal year, the average borrower probably makes at least $600-1200 (i.e., $50-100 per month) in payments. If we assume $1000 per borrower and that only half (20 million) of the borrowers are in active repayment, that's $20 billion in payments on a $1.2 billion cost.

As noted, I do not have access to ED data, but I think the above numbers should give you a sense of how absurd the claim is.

When asked in another email whether the claim may have something to do with a misinterpretation of the language of the report, Ballmann responded with an example of the complexities of financial terminology:

I'm an accountant originally (former CPA) and I could go on and on about the accounting for student loans, or distinguishing between spending and investment when it comes to the federal budget. An important consideration with ED's Pell grant program, for example, is that while the Pell grant program clearly represents money out the door, the total Pell grant to the average college graduate is likely around $15-20K over their college career, but then the average college graduate makes $1 million more over their lifetime than a HS graduate, so that creates an incremental $200-250+K in federal income tax revenues, but that doesn't get taken into account for federal budget scoring. You could make the same argument for loans as well, although the math is obviously different.

Lead Stories also reached out to the Department of Education, which confirmed that it received our inquiry, about the claim. We will update this fact check with any relevant response.