Were the movies of nuclear tests conducted in the 1950s by the United States fake because the cameras and film used to capture the images were not destroyed by the explosion or the radiation? No, that's not true: The cameras and film used to capture the images were positioned at a safe distance from the explosion and designed to avoid destruction by the blast or radiation.

The claim appeared in a video on YouTube (archived here) published by podcaster Joe Rogan on July 23, 2023, under the title "Joe Rogan: 'They FAKED Old Nuclear Test Videos?!'" The video's caption said:

Marc Andreessen is an entrepreneur, investor, and software engineer. He is co-creator of the world's first widely used internet browser, Mosaic, and cofounder and general partner at the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

Clip taken from JRE #2010 w/ Marc Andreessen

Host: Joe Rogan

Guest: Marc Andreessen

Producer: Jamie Vernon

This is what the post looked like on YouTube at the time of writing:

(Source: YouTube screenshot taken on Wed July 26 15:24:06 2023 UTC)

The Joe Rogan Experience

The nearly eight-minute clip is from an episode of the podcast "The Joe Rogan Experience." During the show, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen discusses various conspiracy theories surrounding the U.S. nuclear program. After showing a video of a house being destroyed by a shock wave in the testing of a nuclear weapon during Operation Upshot-Knothole Annie in 1953, Andreessen and Rogan have this exchange:

Andreessen: OK, so here's the question, right? ... So, what happened to the camera?

Rogan: You son of a bitch. You son of a bitch.

Andreessen: How is that happening and yet the camera is like totally stable and fine?

Rogan: Oh, my God.

Andreessen: By the way, the film is fine. The radiation didn't cause any damage to the film.

Click below to watch their conversation on YouTube:

Atomic Heritage Foundation

Lead Stories found a cleaner version of the nuclear explosion video on YouTube, provided by the nonprofit Atomic Heritage Foundation, which operates The National Museum of Nuclear Science & History. You can watch it below:

Los Alamos National Laboratory

To get an answer to the claim that the videos were faked because the camera and film were undamaged by the blast and radiation, Lead Stories reached out to Alan Carr, the senior historian at Los Alamos National Laboratory, where the U.S. nuclear program was established in 1943 and continues to operate. In a LinkedIn message on July 26, 2023, Carr said:

This suggestion that tests were faked based on cameras not being destroyed is absurd to the point I have to wonder if it's a joke.

Cameras were placed at distances where they were quite safe from blast effects.

For the house video, the building was more than 3,600 feet (1,100 meters) from ground zero, or about seven-tenths of a mile, according to the Atomic Archive.

Camera towers

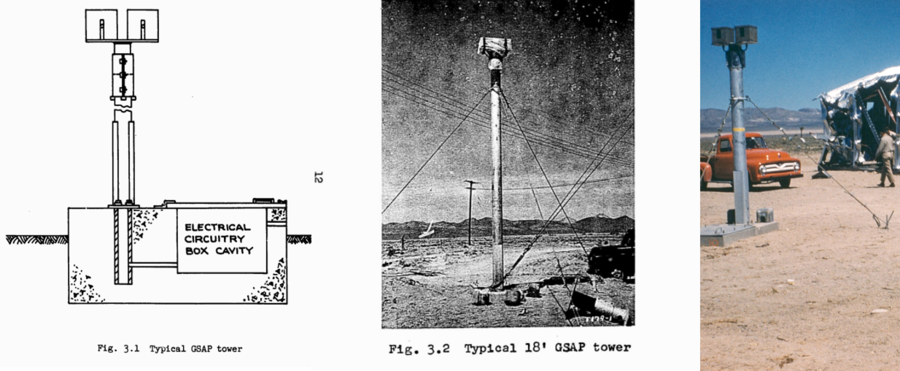

The camera towers used to shoot the videos were built to stand steady and withstand the blast wave from the nuclear explosion. Lead Stories couldn't directly find camera tower specifications for 1953's Operation Upshot-Knothole, which is what the house video is from. However, we were able to pin down the details of Operation Teapot in 1955, which used the same towers to hold the cameras. The information appears on page 11 of a U.S. military PDF covering the technical photography for the operation. Section 3.2 of the document said:

In order to get above the dust raised by the shock wave, all cameras were placed on towers. These were the same towers used for the Military Effects Program on Operation Upshot-Knothole and were graciously loaned to the project by AFSWP [Armed Forces Special Weapons Project]. A typical tower is shown schematically in Figure 3.1. The tower consists of a guyed monopole with a small camera platform on top. The pole is an 8-inch steel pipe and is set in a reinforced concrete base. A cavity in the base houses the electrical control circuitry and batteries. Both 18 and 10-foot towers were used by the project.

The three images below are examples of the towers, from a schematic figure to photographs:

(Source: Armed Forces Special Weapons Project and National Museum of Nuclear Science & History screenshots taken on Wed July 26 2023 UTC)

In all, 48 cameras were used in Operation Teapot and were operated at distances from ground zero of 2,750 feet to 10,500 feet (half a mile to two miles), page 6 of the PDF said.

In a separate July 26, 2023, email, Carr said additional steps were taken to protect the cameras from nuclear blasts. He said:

Cameras were placed inside lead-lined boxes on sleds, where they captured images of the blast on mirrors that were directly exposed to the light and blast.

Page 13 of the PDF on technical photography for the 1955 operation reinforced the protective measures taken for the cameras:

In order to avoid film fogging due to nuclear radiation, cameras were placed Inside steel boxes fitted with 2 1/2-inch thick lead shields. All external cameras were shielded In this manner except [for three of the camera stations].

The protective boxes for the cameras can be seen in the schematic figure and pictures above.

Film producer and author Peter Kuran, who won an Academy Award for developing film preservation techniques while making the documentary "Trinity and Beyond: The Atomic Bomb Movie," told Lead Stories in a July 26, 2023, email that other factors also played into the images that were captured. He said.

The type of film used was very slow and not very sensitive to radiation yet these cameras still needed a couple of inches of lead around them. The camera set ups were designed to stay in place and handle the blast pressure.

Kuran added, "However, not every camera made it and if the camera was blown off its mount, the radiation would ruin it."