STORY UPDATED: check for updates below.

On November 10, 2021, Lead Stories published a fact check about an article published by the British Medical Journal (BMJ) on November 2, 2021. In response, the BMJ published an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg on December 17, 2021, calling our fact check "inaccurate, incompetent and irresponsible."

We addressed their concerns in a December 18, 2021, article, going over their objections point-by-point. On January 19, 2022, the BMJ published another article titled "Facebook versus the BMJ: when fact checking goes wrong," this time accusing Facebook (and Lead Stories) of "censorship." BMJ selected quotes from an expert who suggests fact-checking contractors like Lead Stories have an "inherent conflict of interest" and that we are under "pressure ... to come up with problems and to appear to help solve them."

We disagree: We think that when in the middle of a global pandemic an article from a respected medical journal goes viral on social media and gets wildly misinterpreted by many people who might make health-related decisions based on it, adding a warning label to it and a link to accurate additional context is simply the responsible thing to do.

In this article we want to give more context about why we decided to fact check the story, what the "missing context" label stands for (and why it does not constitute "censorship") and why we are disappointed in the BMJ's apparent violation of their own published journalistic standards.

Why did we fact check this particular story?

The subhead on the main page of the Lead Stories website reads "Just Because It's Trending Doesn't Mean It's True -- Fact checking at the speed of likes since 2015," and that explains our mission quite well: We go after viral misinformation. Our "How We Work" page explains in great detail what tools we use and how we decide what content to fact check. We mainly look for checkable content that is viral and harmful. Under harmful we include content that might cause:

... negative health impacts, reputational damage, ... minimizing or exaggerating real problems, ... distorted understanding of current events, people getting wrongly blamed for things, false evidence being used to support larger conspiracy theories...

So, was the article viral? According to CrowdTangle data from November 18, 2021, the story had well over 120K engagements on Facebook:

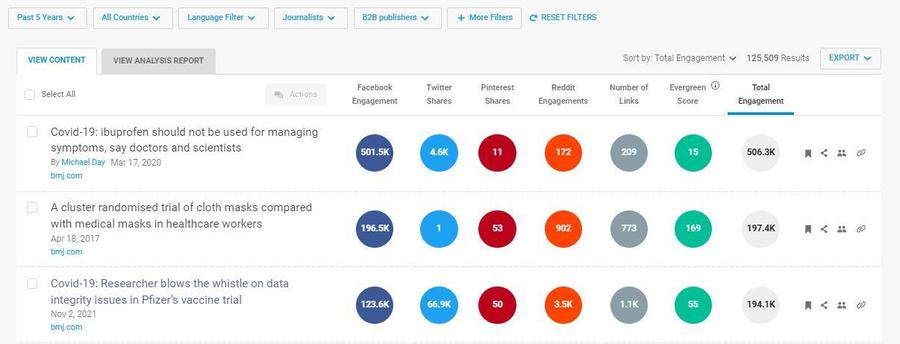

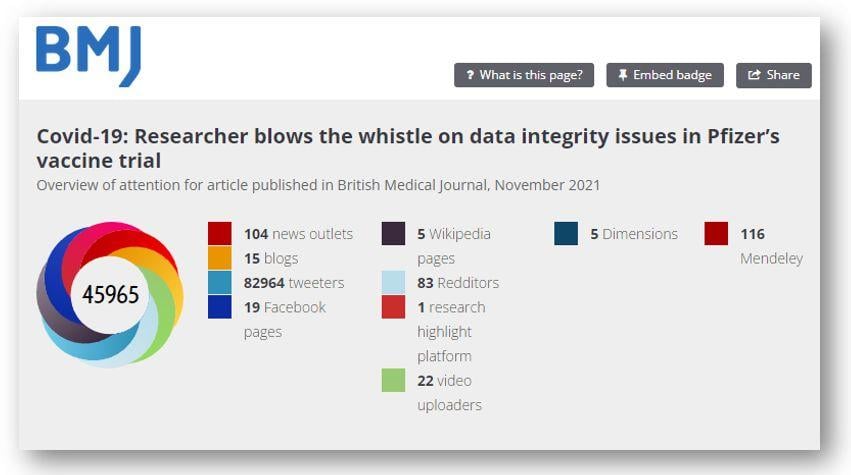

BuzzSumo lists the story as the third most engaged-with BMJ story of the past five years (and their most shared story ever on Twitter) :

Altmetric, a site measuring the online impact of scientific articles, shows the story was linked to or mentioned in many, many places:

So it most definitely was viral.

But was it also harmful, with the potential to impact health, reputations and putting blame on the wrong people? Or being used to support conspiracy theories?

The BMJ noted in their open letter that they made no "assertions of fact" that were wrong, and that the story underwent "legal review," "external peer review" and "high level editorial oversight and review." The story indeed properly notes all the allegations in the story are about things that happened at Ventavia, a subcontractor running three testing sites (out of 153) in the larger trial of Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine. It never directly accuses Pfizer staff of wrongdoing or Pfizer of taking any illegal or nefarious action as a company.

But it does open with a quote from Albert Bourla, the CEO of Pfizer, and it mentions the company 24 times by name. That perhaps explains why in response to the story the hashtag #pfizergate went viral on Twitter (and not the hashtag #ventaviagate).

The official Twitter account of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine seems to have interpreted the article to mean it was Pfizer who did all the things mentioned in the story:

BREAKING: Bombshell report in British Medical Journal "raises serious questions" on Pfizer vaccine trial.

-- Sputnik V (@sputnikvaccine) November 2, 2021

BMJ:"Pfizer falsified data, unblinded patients, employed poorly trained vaccinators, was slow to follow up"

Not a word on this in other Western media😳https://t.co/NoQPK22ixa

So did this tweet:

Pfizer guilty of fraud, data manipulation and more, according to the British Medical Journal #BMJ whilst reports surge alleging Project Veritas and several journalists have received visits from the #FBI seeking a diary poss c/o Ashley Biden #Pfizergate https://t.co/TguXEahEJC

-- Nic - Mitchell Moneypenny (@nic_moneypenny) November 5, 2021

Based on the BMJ report, French politician Florian Philippot even called for a suspension of the use of the Pfizer vaccine out of concern for public health:

Suite à ces révélations sur Pfizer d'un lanceur d'alerte dans le très sérieux @bmj_latest Olivier Véran doit suspendre le produit et demander une ré-évaluation de son AMM même conditionnelle.

-- Florian Philippot (@f_philippot) November 3, 2021

La santé publique avant tout ! Stop aux gros sous !#Pfizergate https://t.co/FXdepcfTrK

These tweets are just three examples of people interpreting the BMJ article as being about Pfizer and wildly overstating what the actual allegations in the story were. The BMJ article never mentions "fraud" and the only place where any details about data falsification are mentioned is this part:

In a list of 'action items' circulated among Ventavia leaders in early August 2020, shortly after the trial began and before Jackson's hiring, a Ventavia executive identified three site staff members with whom to 'Go over e-diary issue/falsifying data, etc.' One of them was 'verbally counseled for changing data and not noting late entry,' a note indicates.

It doesn't say what data was falsified (or even that it actually happened), how much of it was falsified or how serious an issue it was, nor does it mention what happened to the data afterwards. Was it corrected? Removed from the trial? Used anyway? The BMJ doesn't say.

It also speaks of "potentially unblinding" and "inadvertent unblinding" that "may have occurred" but without clarifying if it actually was proven to have happened and at what scale. There are also allegations of "vaccines not being stored at proper temperatures" and "mislabelled laboratory specimens" but without quantifying how many doses or specimens were involved and what happened to them. Were they used? Destroyed? Included in the study? Readers are left guessing.

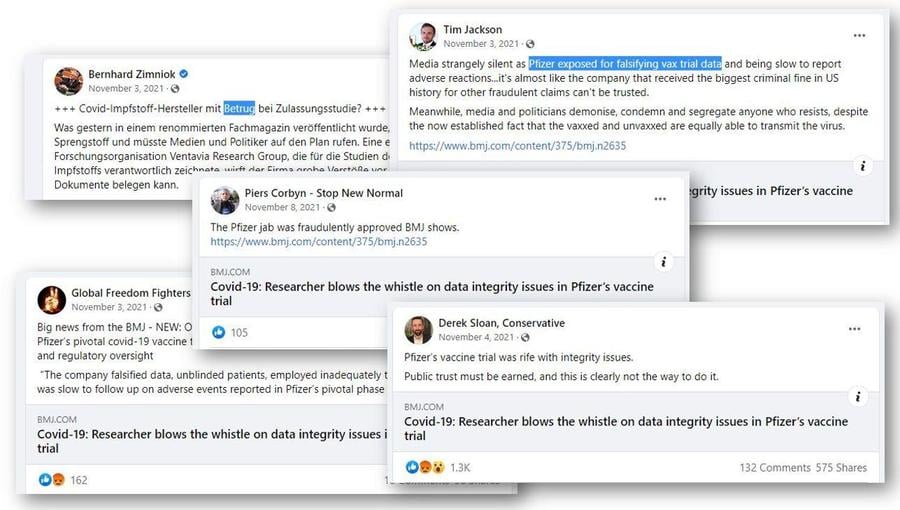

But that didn't stop Facebook users from wildly misinterpreting and overstating what the article said. Here's a Facebook post with more than a thousand engagements that concluded the *entire* trial was "rife with integrity issues" based on the article. Or this post that makes it seem like it was Pfizer doing things instead of their subcontractor Ventavia. Or another (now removed) post that surmised from the article that the Pfizer vaccine had been "fraudulently approved" even though the BMJ didn't write that. Or this post from a German politician using the word "betrug" ("fraud") to describe the allegations in the article. Or this Irish politician claiming based on the article Pfizer was exposed for falsifying data.

We might not be doctors but we do know a thing or two about journalism: When your headline or article causes a large number of readers to conclude things you didn't write, you are doing something wrong.

Which is why we decided that a fact check was warranted and appropriate here.

Use and misinterpretation of the story by bad actors

The article wasn't just being misunderstood by social media users. Some people also deliberately used the story to spread misinformation. Note that just because a story is shared or commented on by people with a questionable track record for accuracy, that is not by itself enough reason for a fact check. But we think the examples below illustrate even more how easy it was to misinterpret this particular story.

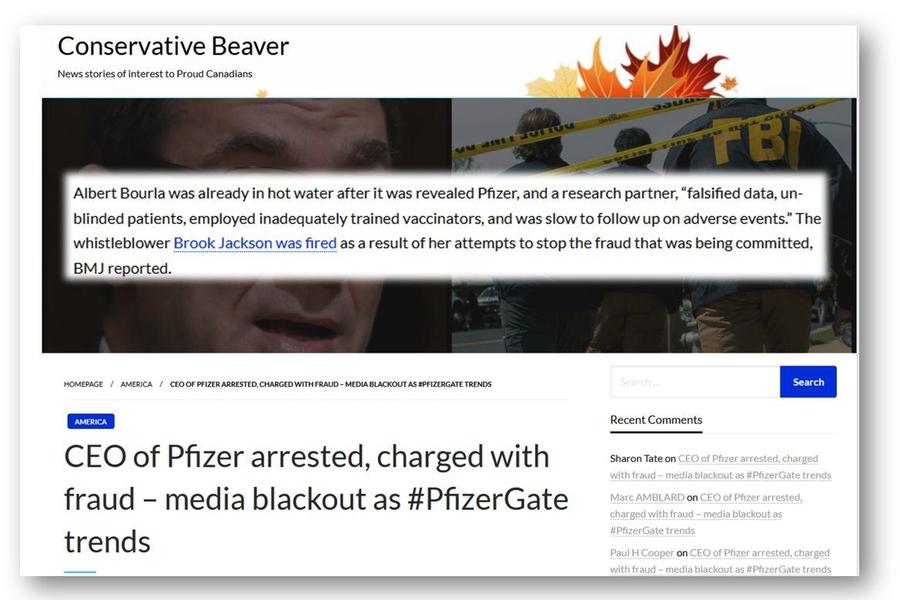

The Conservative Beaver, a Canadian fake news website, received almost 50,000 engagements on Facebook according to CrowdTangle data with a made-up story that falsely claimed the CEO of Pfizer had been arrested for fraud. It was based in part on quotes of the BMJ story and also linked to it. Predictably the story spread like wildfire among anti-vaccine activists.

(Source: composite screenshot made by Lead Stories based on archive.org copy of the Conservative Beaver story)

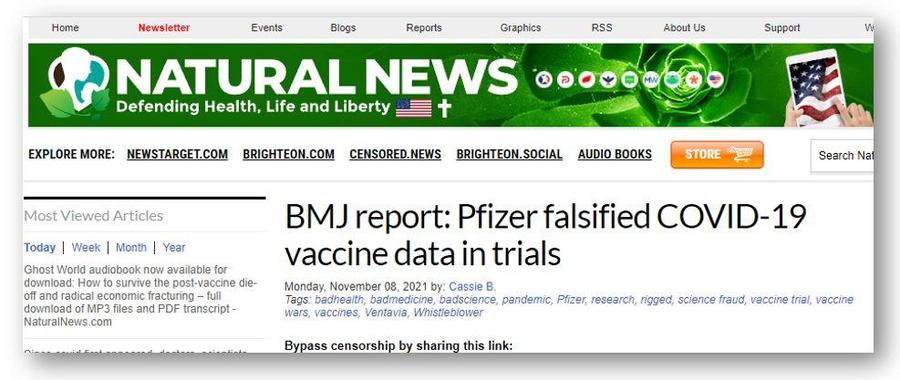

Natural News, described by Vox.com as "one of the internet's oldest and most prolific sources of health misinformation and conspiracy theories," pointed to the BMJ report to make the unproven claim (archived here) that Pfizer had falsified data (which, again, the BMJ did not actually make).

(Image source: screenshot of Natural News taken by Lead Stories on January 27, 2022)

The Free Thought Project, described as a site with an "abysmal fact check record" by Media Bias / Fact Check, also flat-out claimed in their headline (archived here) that the BMJ report said Pfizer had "faked vaccine data" (which again, the BMJ didn't actually say):

(Image source: screenshot of The Free Thought Project taken by Lead Stories on January 27, 2022)

On the day of publication the BMJ story was also copied word-for-word (archived here) on the Defender, the website of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s Children's Health Defense Fund. According to NewsGuard the website is one of the major anti-vaccine disinformation sites in the world and Kennedy is included in the (in)famous "Disinformation Dozen" identified by the Center for Countering Digital Hate as being responsible for a large part of online vaccine disinformation.

(Image source: screenshot of the Defender taken by Lead Stories on January 26, 2022)

The Defender did add one introductory sentence just below the title that added the claim that Pfizer falsified data (which again, as we pointed out earlier, the BMJ did not make).

They also kept intact the byline of Paul D. Thacker, the author who originally wrote the BMJ piece, claiming they were copying the piece from the BMJ based on a CC BY NC (Creative Commons NonCommercial) license:

Originally published by The BMJ Nov. 2, 2021, written by Paul D. Thacker, investigative journalist, reproduced here under the terms of the CC BY NC license.

This was not the first BMJ piece from Thacker copied by the Defender this way. The site has an entire author profile page for him with the oldest article listed dating back to July 2021:

(Image source: screenshot of the Defender taken by Lead Stories on January 26, 2022)

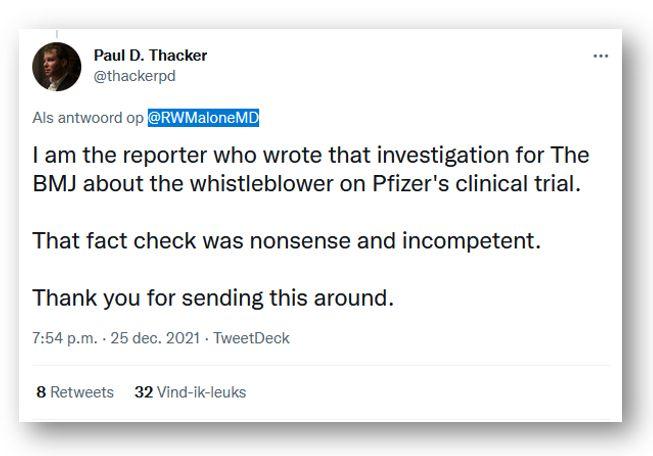

When Lead Stories inquired via Twitter if Thacker was OK with being listed as an author on a major anti-vaccine website he did not answer that question but said all the BMJ's COVID-19 stories are made freely available to any website and called us a "moron," after which he blocked us:

He did seem OK with the BMJ's criticism of our fact check being shared by Dr. Robert Malone (recently banned from Twitter for violating their COVID-19 misinformation policies) because he explicitly thanked him for it:

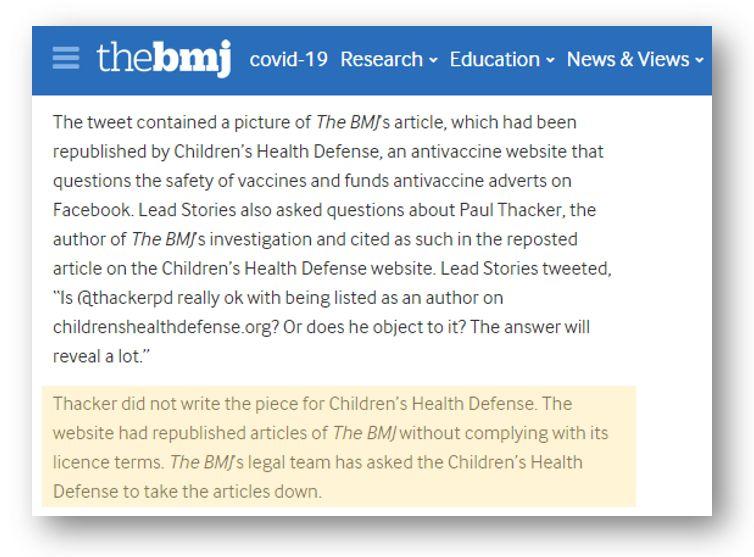

Note that the BMJ to their credit later did make an attempt to stop their content being used on "an antivaccine website that questions the safety of vaccines and funds antivaccine adverts on Facebook":

That's quite different from Thacker's initial "made freely available to any website, you moron" stance.

Lead Stories was not alone in noting the BMJ story had issues

Medpage Today, a publication covering medical news, parodied the BMJ's headline with an article by Cheryl Clark titled "Experts Blow Whistle on Alleged COVID Vaccine Whistleblower Claims," and quoted an expert describing the allegations in the story as a "vague kind of hand waving":

However, several vaccine experts familiar with COVID vaccine clinical trials questioned the article's accuracy, and advised people not to believe it outright.

'It's all this sort of vague kind of hand waving; I have no idea whether any of this is true, nor do you,' Paul Offit, MD, of Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and a member of the FDA's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, told MedPage Today.

They also noted the author of the BMJ story did not seek comment from Ventavia before publication:

Asked for a response, Ventavia spokeswoman Lauren Foreman objected to The BMJ article, written by investigative journalist Paul Thacker. She said Thacker's article did not include any of the evidence the accuser claims she had, and that he did not contact Ventavia for a response before publishing. (Attempts to reach Thacker were unsuccessful.)

Nor from Pfizer:

In a statement, Pfizer said it was 'disappointed by the recent article published by the British Medical Journal that failed to contact us prior to publication and selectively reported certain claims with the goal of undermining confidence in a vaccine that has been given to hundreds of millions of people worldwide.'

Science Based Medicine's Dr. David Gorski published an article asking "What the heck happened to The BMJ?", describing the report as "a highly biased story embraced by antivaxxers, with a deceptively framed narrative and claims not placed into proper context," summarizing the article as:

Basically, Thacker takes fairly uncontroversial observations (e.g., that the FDA is underfunded and doesn't audit sites as often as it should) ... and combines them with vague reports of what are probably mostly minor violations played up as huge, impactful violations

While also questioning the motives of the author:

Thacker being Thacker, trying to turn a molehill into the proverbial mountain, as long as it fulfills his purpose of demonizing big pharma.

Gorski concludes:

If one of your editors and one of the freelance reporters that you've been publishing have their own pages at an antivaccine website, which republishes their work enthusiastically to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt about vaccines and COVID-19 public health interventions, you really are doing things very, very wrong and contributing to pandemic misinformation in a huge way, given The BMJ's status.

Funnily enough, even the Twitter account for the Russian Sputnik V vaccine later also acknowledged some of the "alleged violations" may have been exaggerated:

Some #Pfizergate posts may exaggerate alleged violations. Bigger issue is that Pfizer confirmed that its efficacy falls to 47% in 5 mo vs Delta leading to spike in breakthrough cases & this has to be addressed via heterologous boosting by another vaccine. https://t.co/k1tzgwIMzl

-- Sputnik V (@sputnikvaccine) November 4, 2021

A story by Joedy McCreary on CBS17.com (archived here) titled "Fact check: Report questioning Pfizer trial shouldn't undermine confidence in vaccines," quoted Thacker and Dr. Jill Fisher on the issue of the BMJ report being used to further a vaccine skeptic narrative:

The report was making rounds on social media, with vaccine skeptics pointing to it as justification for their skepticism.

Even Thacker acknowledged that 'people are going to use this to push a political position because that's what they're interested in.'

But Fisher -- who has authored books on the subject of clinical trials and was quoted in Thacker's story -- says that's the wrong takeaway.

'I think that's definitely a narrative that's out there,' she said. 'And I don't think that's necessarily a fair narrative.'

Belgian French-language public broadcaster RTBF filed a story titled "Y a-t-il réellement un 'Pfizergate' ? Des essais cliniques du vaccin anti-Covid sont-ils remis en question?" ("Is there really a 'Pfizergate'? Have the clinical trials of the anti-Covid vaccine been put into question?") In it they say:

The article published by Paul D. Thacker relies on one principal source and two anonymous ones. The evidence mentioned in the publication like the photos or copies of email exchanges are not documented.

Contacted by Numerama, a news website about IT and the digital, the Ventavia company indicated 'not having been contacted [by the author] before publication.' And yet this is an important part of the journalistic approach. When an investigation seriously accuses a person or company of wrongdoing it is crucial to speak with the accused person or company to confront them with the evidence and to give them the opportunity to provide an explanation about any allegations there may be.

(Translated from the original French by Lead Stories)

Miguel Hernán, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at Harvard, tweeted

Shame on BMJ for irresponsible reporting.

-- Miguel Hernán (@_MiguelHernan) November 3, 2021

The serious data problems found with Ventavia's management of Pfizer's vaccine trial:

likely make the vaccine look worse than it actually is

affect 3 of 153 sites

You need to lead with this information, @bmj_latest.

So disappointing. https://t.co/5PweQQ0LTF

What missing context means to fact checkers

Some people might have the impression that fact checking is only concerned with pointing out and exposing false information. That would not be correct. It is perfectly possible to create an entirely false impression by only using true facts. Take this little (fictional) story as an example:

BREAKING: Wayne A. Dubanowski was seen by multiple witnesses loitering near the scene of a deadly house fire holding an axe in his hands. Police sources say they suspect arson and possible murder took place and they are currently collecting evidence. Reports say it was no coincidence Dubanowski was found at the crime scene, according to an investigation he was connected to several people who were also seen there and his behaviour led many onlookers to suspect his presence was clearly linked to the fire.

Every statement in this story could be completely correct and factual but based just on this information some readers might think poor Wayne was a ruthless serial killer instead of a fireman who came to put out the blaze.

There are countless stories, videos, memes, etc. out there that use nothing but completely factual information but that get scrutinized by fact checkers anyway because they are very misleading. Think of all the bad takes about VAERS data or stories comparing absolute numbers of deaths, hospitalization or infections in vaccinated vs. unvaccinated people while completely ignoring the relative sizes of these groups in the population.

Precisely for this reason Facebook's rating options for fact checkers include an option for "Missing Context" which is defined as:

4. MISSING CONTEXT. Content that may mislead without additional context.

As the examples at the top of this article illustrate, "may mislead without additional context" clearly wasn't hypothetical here, so this was the option Lead Stories went with.

The program policies spell out that the only consequence of a "Missing Context" rating is a label, since all the other possible consequences are tied to different ratings:

The label that appears on "Missing Context" content can easily be clicked away or ignored:

The goal is to warn of potentially misleading content and offer additional information.

It is similar to the standard COVID-19 information box that appears under some posts determined by Facebook to contain content related to the disease.

Fact checking labels are not the same as censorship

The BMJ article about their issues with the fact check characterizes these labels as "censorship" and describes the appeals process as "opaque":

Kaplan was not the only Facebook user having problems. Soon, several BMJ readers were alerting the journal to Facebook's censorship. Over the past two months the journal's editorial staff have been navigating the opaque appeals process without success, and still today their investigation remains obscured on Facebook.

Our contact page lays out the entire "opaque appeals process":

If something you created or published has been rated by Lead Stories under Facebook's Third-Party Fact Checking Partnership and you wish to appeal the rating or notify us that you published a correction:

- First make sure you have read Facebook's guidelines for publishers (especially the section about appeals/corrections and the need to publish a correction notice)

- Do NOT delete the article/post/image/video (this makes it impossible to change the rating)

- Do NOT change the URL of the article/post/image/video (this makes it impossible to change the rating)

- Then send a message to: [email protected] including the link to the fact check and the link or post you are appealing about or which you have corrected. Facebook has provided email templates you can use to make sure your message includes all the relevant information.

Summarized: Send us an email letting us know you published a correction or convincing us your article was not misleading. That's it. That's the process.

As to the censorship allegations: Censorship usually involves content being removed or made unavailable, it does not involve information being added.

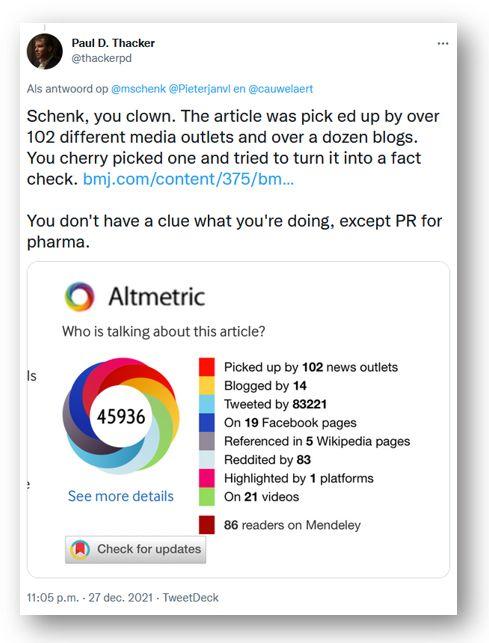

At the time of writing Facebook's developer tools show the BMJ story received 123,770 likes, shares and comments. The BuzzSumo statistics at the top of this article show it was one of the most engaged-with stories the BMJ ever published. Before blocking me on Twitter the article's author Paul D. Thacker was tweeting at me about how many media outlets picked up the story:

If this was "censorship" it failed miserably.

Why we are disappointed in the BMJ's reaction so far

If you have been following along, in this article we've quoted Paul D. Thacker tweets three times so far. In one he called me a "moron," in another he called our fact check "nonsense and incompetent" and in the third one he referred to me as a "clown" and our activities as "PR for pharma." For good measure here is a fourth one in which he repeats those allegations along with claims that Lead Stories is a "nonsense opinion site":

So it was quite surprising to us that the BMJ called some of our comparatively mild tweets "inflammatory" in their article:

On 20 December Lead Stories also sent a series of inflammatory tweets after publishing its response to The BMJ's open letter.11 It said, "Hey @bmj_latest, when your articles are literally being republished by a website run by someone in the 'Disinformation Dozen' perhaps you should be reviewing your editorial policies instead of writing open letters."12

The tweet contained a picture of The BMJ's article, which had been republished by Children's Health Defense, an antivaccine website that questions the safety of vaccines and funds antivaccine adverts on Facebook.

Especially since the "inflammatory" tweet in question seems to have been the one that spurred them into finally taking action against Children's Health Defense for copying their story:

The BMJ's legal team has asked the Children's Health Defense to take the articles down.

However the BMJ seems to have ignored the second part of the tweet in their response:

Hey @bmj_latest, when your articles are literally being republished by a website run by someone in the "Disinformation Dozen" perhaps you should be reviewing your editorial policies instead of writing open letters.https://t.co/p6PJjZ112v pic.twitter.com/ExLfOPePRT

-- Lead Stories (@LeadStoriesCom) December 20, 2021

The link in that tweet actually went to the BMJ's editorial policies about "Criticism of health professionals," which state (among other things):

The BMJ has guidelines on articles in which the health professionals are clearly identified and those in which they are not, and some elements are common to both:

• Those accused of wrongdoing have the right to a proper investigation using due process;

• 'Trial by media'--including The BMJ--cannot constitute due process;

One would imagine a proper investigation using due process would involve actually contacting the accused before publishing anything. Simply publishing allegations by a whistleblower and leaving it at that sounds a lot like "trial by media" to us.

Indeed, in the very article lamenting about "when fact checking goes wrong" the BMJ admits to contacting Ventavia, Pfizer and the FDA only after publishing their article (and, incidentally, after our fact check was published):

After publication, and as reported in a linked rapid response on bmj.com, The BMJ contacted Ventavia, Pfizer, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to better clarify the scope and implications of the problems identified at Ventavia and what corrective measures had been taken.

One would think that clarifying the "scope and implications of the problems" and "what corrective measures had been taken" would deserve more prominent placement than what is currently the second page of the comments section:

(Screenshot take by Lead Stories on January 27, 2022 illustrating the position of the rapid response in question)

We applaud the BMJ for their attempt at adding more context to the story. We would just like to encourage them to make it a little more prominent. Because when important context is left out or hidden, misunderstandings happen. Context matters!

Addendum:

"Misinformation is often a technically correct fact that is taken out of context, creating a narrative on its own. Every piece of emerging evidence deserves to be reported with due care--especially if it is published by a credible source such as a leading medical journal."

Creating misinformation: how a headline in The BMJ about covid-19 spread virally doi:10.1136/bmj.m2384

(Please note that this is from a 2020 letter published in the BMJ about a different BMJ headline)

(Editors' Note: Meta is a client of Lead Stories, which is a third-party fact checker for the social media platform. On our About page, you will find the following information:

Since February 2019 we are actively part of Meta's partnership with third party fact checkers. Under the terms of this partnership we get access to listings of content that has been flagged as potentially false by Meta's systems or its users and we can decide independently if we want to fact check it or not. In addition to this we can enter our fact checks into a tool provided by Meta and Meta then uses our data to help slow down the spread of false information on its platform. Meta pays us to perform this service for them but they have no say or influence over what we fact check or what our conclusions are, nor do they want to.)

Updates:

-

2022-01-31T23:55:36Z 2022-01-31T23:55:36Z Addendum added