Does the vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella cause measles? No, that's not true: The claim on social media ignored basic principles of how these vaccines work. It failed to distinguish between potentially deadly strains of the virus and its weakened version, used in the shots to help healthy populations build immunity against this disease.

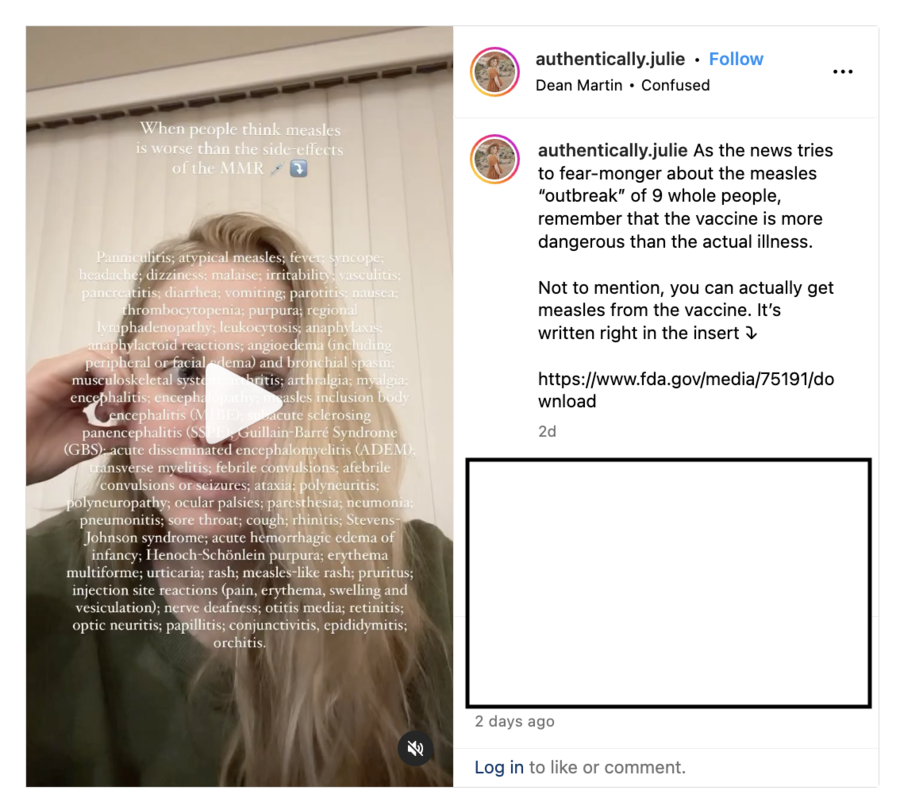

The claim appeared in a post (archived here) on Instagram on January 20, 2024. It opened:

As the news tries to fear-monger about the measles "outbreak" of 9 whole people, remember that the vaccine is more dangerous than the actual illness.

Not to mention, you can actually get measles from the vaccine. It's written right in the insert ⤵️

https://www.fda.gov/media/75191/download

This is what it looked like at the time of writing:

(Source: Instagram screenshot taken on Tue Jan 23 16:42:30 2024 UTC)

The instagram post implied that the MMR II vaccine mentioned in the specific piece of the FDA documentation in the post causes the same diseases it aims to protect from.

However, that falsely equated the viral disease and the vaccine's viral components.

MMR II (archived here) is a type of MMR vaccine manufactured by Merck & Co, Inc. Just like several other vaccines from this category, it does contain a live measles virus, but, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasizes, it is not the same as wild strains (archived here) -- it is an attenuated, or weakened, version of the virus.

The website of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (archived here) explicitly says:

The vaccine does not cause measles.

The website of Johns Hopkins health care facilities (archived here) reads:

The vaccine contains a live but weakened form of the measles virus that is designed to create immunity without causing full-blown illness. In children with normal immune systems, the vaccine will not cause full-blown measles.

The website of the American Society for Microbiology (archived here) explains how MMR vaccines work:

Replication of the attenuated virus in immune cells is essential to develop an effective immune response. The beauty of vaccination with a live vaccine is this 'play-acting' of natural infection, in which a safe, limited version of infection induces a full, robust and lasting immune response, which is essentially equivalent to the immune response induced by natural infection. Some children do develop a fever and mild rash 5-12 days after measles vaccination; these symptoms, which usually last for only 1-2 days, are believed to result from replication of the attenuated virus as the immune response develops. Although these symptoms resemble a very mild version of some of the symptoms of measles, it's important to remember that these symptoms do not represent a case of measles.

The American Society for Microbiology additionally writes that sometimes people can test positive after vaccination, but that is due to the development of immunity, not because they have measles.

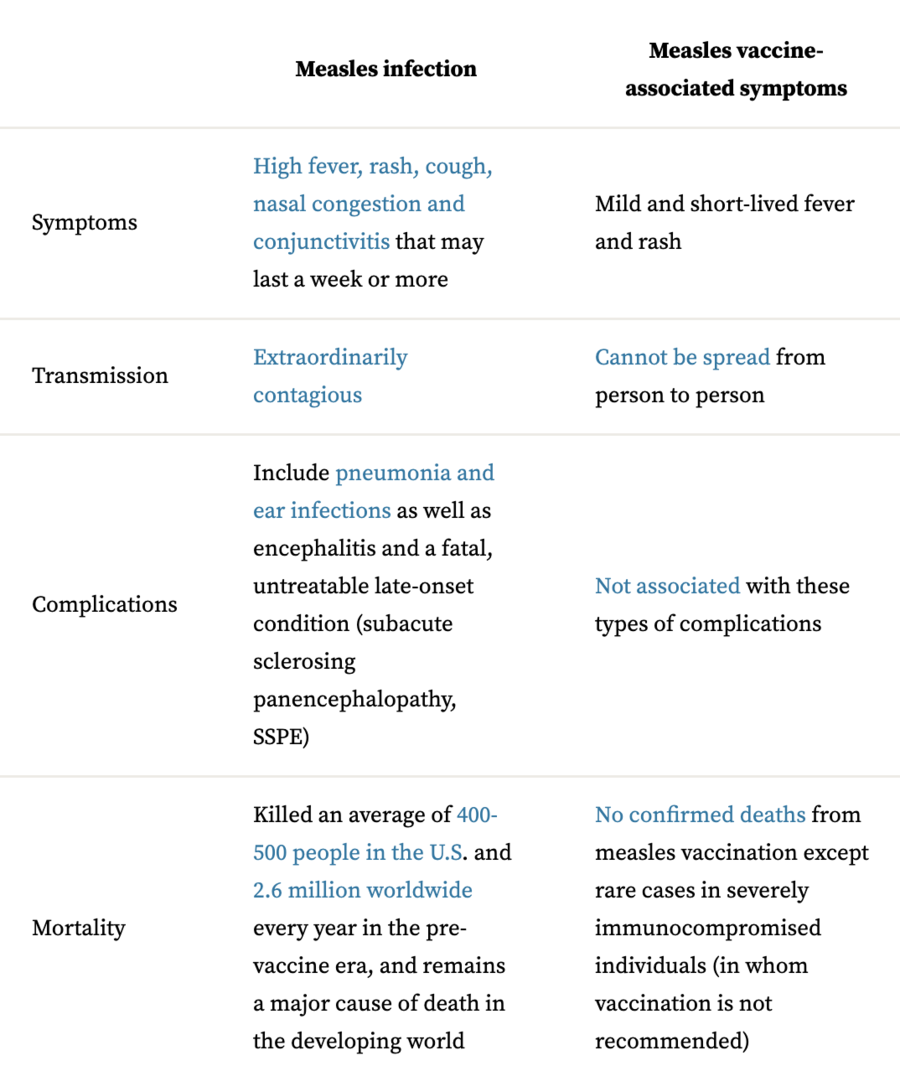

The article on its website also includes a table summarizing the key differences between wild strains of measles and symptoms associated with vaccination:

(Source: asm.org screenshot taken on Tue Jan 23 19:30:17 2024 UTC)

(Source: asm.org screenshot taken on Tue Jan 23 19:30:17 2024 UTC)

People whose immune system is severely weakened due to an illness or treatment don't respond to vaccines the way healthy individuals do, and health authorities warn about it. The CDC describes in detail who should not get the MMR vaccine (archived here), also addressing some specific cases when the benefits of vaccination can be greater than the risks. But the overall recommendation is that most healthy children and adults should get vaccinated.

Contrary to the claim, the Food and Drug Administration package insert (archived here) mentioned on Instagram did not say what the post alleged. Its first paragraph explicitly says that the MMR II vaccine is intended:

for the prevention of measles, mumps, and rubella in individuals 12 months of age and older.

The insert mentions measles-like symptoms such as rash on pages 4 and 5 in the adverse reaction section that includes events reported during clinical trials. But most of what was observed during trials happened at a low rate and was overwhelmingly mild.

Lead Stories went further and researched the term "atypical measles" from the insert. A 1981 article (archived here) explains that it was first recognized in the mid-1960s and that "it occurred in children who were exposed to wild measles virus several years after they were immunized with killed measles vaccine." That was one of the two types of vaccines approved in 1963 in the United States, but four years later, it was removed (archived here) from the market because it was established that the shots based on the inactivated virus did not protect against measles. A 2007 Nature article (archived here) referred to "atypical measles" in the past tense.

Other adverse reactions mentioned in the insert outside of the context of trials may not be related to vaccination at all, as Lead Stories previously wrote. What that list means is that those unwanted events occurred after a shot, but the presence of those entries on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System alone does not establish a causal link.

Infections with wild strains are rare in people who have received two doses of a modern MMR vaccine: roughly 3 cases per 100 people (archived here.)

Had the claim been true, all vaccinated people would have gotten measles, which would indicate that the vaccine doesn't work. But it doesn't happen. Even those who get infected after vaccination "are more likely to have a milder illness, and are also less likely to spread the disease to other people," reads the CDC website. That is another indicator that proves that vaccines offer protection against measles, not infect healthy people with it.

Other Lead Stories fact checks about health can be found here.