Should everyone routinely take dewormer medication, as a post on X suggested? No, that's not true: In certain parts of the world, the World Health Organization recommends periodically giving deworming medication to preschoolers, school-age children, women of reproductive age and those working in high-risk professions. These recommendations are specific to certain regions, primarily sub-Saharan Africa, China, South America and Asia. Otherwise, there is no need for people to deworm themselves routinely.

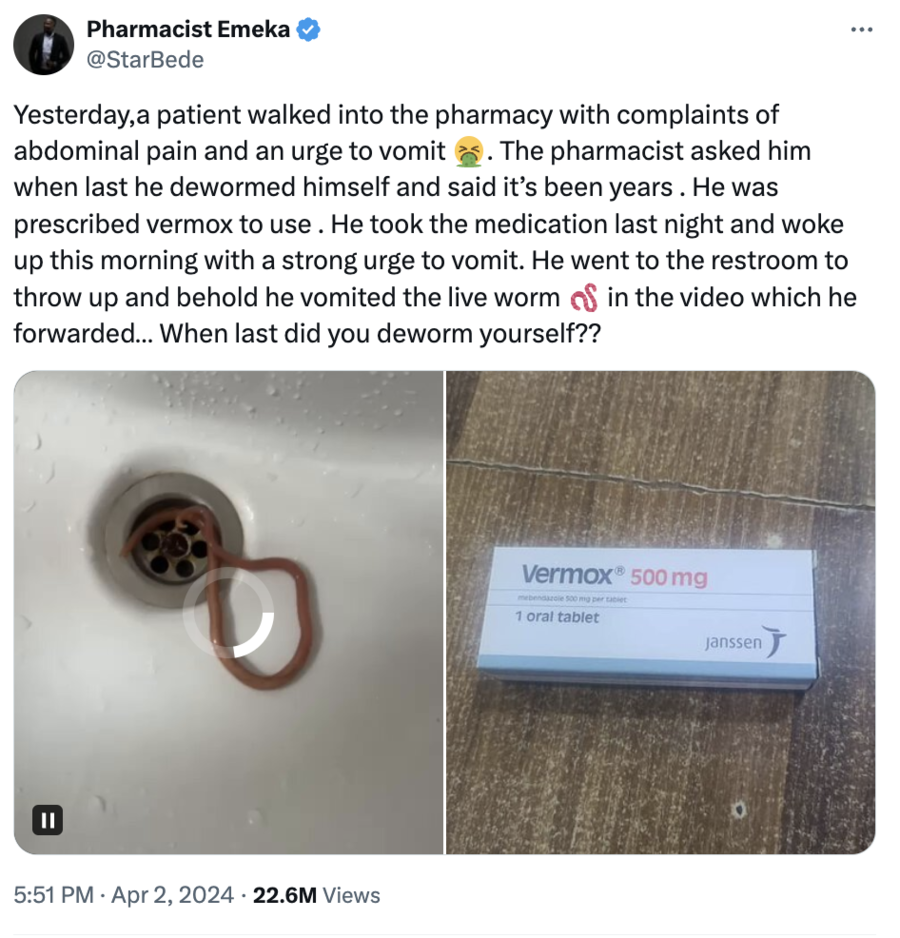

The claim appeared in a post on X (archived here), formerly Twitter, that suggested that people needed to deworm themselves. The text, published on April 2, 2024, read:

Yesterday,a patient walked into the pharmacy with complaints of abdominal pain and an urge to vomit 🤮. The pharmacist asked him when last he dewormed himself and said it's been years . He was prescribed vermox to use . He took the medication last night and woke up this morning with a strong urge to vomit. He went to the restroom to throw up and behold he vomited the live worm 🪱 in the video which he forwarded... When last did you deworm yourself??

Here is how the post appeared at the time of the writing of this fact check:

(Source: X screenshot taken on Fri Apr 5 19:33:21 2024 UTC)

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) published recommendations (archived here) for what it described as "large-scale deworming to improve children's health and nutrition." WHO described the recommendations as "the first evidence-based guideline" that confirms that "deworming decreases and prevents" the severity of infections and can improve children's health and consumption of nutrients.

The guidelines (archived here) recommended chemotherapy (deworming) in areas "endemic for soil-transmitted helminths," or intestinal worms, in children, adolescent girls, people of reproductive age and pregnant people. The highest prevalence of infection (archived here) is reported in sub-Saharan Africa, China, South America and Asia.

Ashleigh Smythe (archived here), a nematologist and a parasitologist at Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, told Lead Stories that people living in the U.S. (with a few exceptions in some poor rural areas in the South) do not need to deworm themselves at all, let alone routinely.

"Only people living in areas that are endemic for roundworms or people living in areas with poor/no sanitation need to be dewormed. The vast majority of people in the U.S., U.K. or Europe do not need to deworm," Smythe told Lead Stories in an email received on April 5, 2024.

As for the worm featured in the post on X, Smythe identified it as likely being the nematode parasite Ascaris lumbricoides (archived here), "which infects millions of people around the world but is very uncommon in 'developed' countries with good sanitation, like the U.S. or U.K."

Taking deworming medication like Vermox, which was also shown in the post on X, can have side effects and should not be taken unless with a doctor's supervision, she said.

"It is not necessary for most people unless they are diagnosed with a parasite for which this treatment would be appropriate," Smythe added.

Globally, the most common infections of intestinal worms are from roundworms, whipworms and hookworms, according to WHO (archived here). Each of these parasites requires a similar diagnostic procedure and responds to the same medicines. The deworming treatment plan is typically a single tablet of albendazole (400 milligrams) and mebendazole (500 milligrams).

Threadworms, another common intestinal parasite, present different characteristics and diagnosis. Typically, WHO recommends ivermectin as a treatment.

Eggs transmit infection via human feces that contaminate soil in areas of poor sanitation. They are not transmitted between humans or from fresh feces, as eggs require three weeks to mature in soil before becoming infected. Once they have infected a host, intestinal worms feed on tissue and can cause malabsorption of nutrients, chronic intestinal blood loss and loss of appetite, WHO writes (archived here).

In addition to the above recommendations, the WHO strategy for control recommends that:

... periodic medicinal treatment (deworming or preventive chemotherapy) without previous individual diagnosis to all at-risk people living in endemic areas. This intervention reduces morbidity by reducing the worm burden.

WHO writes (archived here) that deworming isn't the only solution when managing intestinal worms. Focusing on basic hygiene, sanitation, health education and access to safe drinking water also reduces infection rates in at-risk areas.

Other Lead Stories health-related fact checks can be found here.